Common

Mode Noise

Cleaning Up Problems and Impedance Required

jump to Common_Mode_Choke

Jump down this page to dipole models

This page explains common mode currents. Currents flowing without equal closely spaced return currents

are called common mode currents. Common mode currents cause

conductors to couple to each other. Common mode currents are generally behind

desired EM

radiation and reception. Unwanted common mode currents can also flow through sensitive

equipment, causing RFI, or couple unwanted noise into a system from a noise

source.

We have to be realistic about goals. There has been

an alarming trend to specify unrealistic impedance for common mode choke.

In balanced lines, common mode current flows on both conductors. In balanced lines, unbalanced current levels prove common mode. Balanced currents do not prove the system is free of common mode. Currents can be equal in both conductors even with 100% common mode!

In coaxial cables with shields more than several skin depths thick, common mode flows exclusively on the outside layer of the shield. It is impossible to force common mode currents to the inside of shields more than a few skin depths thick. coaxial lines and shielded wires

See Current Balance

Common

mode currents cause coupling between conductors as well as electromagnetic radiation

(transmitting or receiving). Common mode currents bring RF directly into the

operating position wiring, contributing to equipment interference problems.

Likewise if RF couples in, it also couples out to the antenna. This can increase

noise and interference to desired signals when receiving. Inside the Ham

shack or along the antenna feed line,

common mode currents are responsible for unwanted noise ingress, RFI, RF burns,

and a host of other maladies. Common mode currents effectively bring the radiating

part of the antenna system down along the feed line or the antenna's metallic

supporting structure. Common mode currents can extend all the way to the desk

and station equipment, and even out through power line connections. Problems

flow both ways.

Common mode currents also serve a useful function. In any antenna, common mode currents in the antenna

element(s) are responsible for radiation. From this standpoint we

cannot have radio communications without common mode. Every antenna has common mode current someplace, otherwise it would not radiate.

There

must be enough isolation between "good" system common mode and

undesired common mode to make the undesired effects unnoticeable.

The keyword is unnoticeable, since zero or a universal arbitrary specification

is not realistic. We generally do not want feedlines to noticeably act like

antennas, and we certainly don't want electrical noises in

house wiring or surroundings to infiltrate the antenna. The best idea is to keep

significant or troublesome common mode current levels from our antenna systems out of

sensitive equipment, and reduce noise and unwanted signals making back to the

antenna, where they can override desired signals. Things seem to have gotten

beyond reason, once conducted signals fall below unavoidable space coupling,

further suppression is meaningless. Working systems also have impedance limits

far below test bench limits.

Proper feedline treatment also offers

improved lighting damage immunity. Common mode currents are generally best dealt with at the source or as close to the

source as practical without compromising effectiveness.

Most important of all, cures are generally not a one-size-fits-all solution. The most effective cure and work required is dependent on the specific installation. To understand how a common mode suppressor or choke works and the impedance required, we must understand balance. We must further have a reasonable grasp of circuit analysis and the imnpedance limits of lumped components at radio frequencies, and some idea how things couple at a distance. I'll do my best to describe these limits without being complicated. I can design things that test to very high impedances on a test bench, but they can have no practical use when connected to long random cables.

Most often balance is described only by current in each conductor of a transmission line. This is completely inadequate and can mislead or confuse us. We cannot know balance without knowing voltage, current, and phase.

Perfectly balanced lines and perfectly unbalanced

lines all have equal and opposite currents entering and leaving the conductors

at each end, as can lines that are out of balance. All properly operating

two-conductor transmission lines, coaxial or parallel wire, carry equal and

exactly opposite phase currents in the two conductors. Non-radiating coaxial

lines and parallel lines (twin lead or ladder line) both have exactly equal and

opposite flowing currents entering or leaving each conductor at any given end of

the transmission line. (See coaxial

lines at this link)

The only thing determining the gender of balance

is the electric field to space surround the line, or the conductor voltages to

"ground" or space around the line.

We can establish these rules for properly operating transmission lines:

coaxial and balanced lines both have equal and opposite currents in each conductor

perfectly unbalanced lines have zero electrical field (voltage) outside the line fringing to space, other objects, or to "ground"

perfectly balanced lines have equal and opposite electric fields fringing out to space around the line or coupling to "ground". These fields, for all practical purposes, vanish several conductor spacing's from the transmission line

Dipoles and doublets are inherently balanced antennas. A relatively symmetrical antenna installation will have very little common mode introduced by the antenna, even if the antenna isn't perfect. Problems can be created by the antenna or feedline layout, but this usually demands a fairly significant construction or layout error. Most balance problems, when using balanced feeders on dipoles or doublets, are generated at the tuner or balun. Non-symmetrical antennas, such as off center fed antennas or end fed antennas, create severe common mode issues. The further the feeder is offset from center, the worse the common mode issue. This means center fed doublets are least problematic, off-center-fed antennas in between, and end fed antennas are the worst possible common mode problems. As a matter of fact, end fed antennas are 100% common mode at the feedpoint!

Coaxial lines feeding less than perfectly unbalanced loads are subject to common mode. Coaxial common mode currents, because of electrical laws (look up Lenz's law and descriptions of skin effect) appear on the shield's outside layer. Anything inside the cable has to be differential mode!

There are two ways to significantly reduce or eliminate common mode. As one solution, generally best at HF, we can install a good current balun or common mode choke at the proper position along the feedline. At VHF or even at upper HF in single band or odd harmonic operation, with a feedline spaced away from other things, we can simply ground the feedline shield about 1/4λ (or 3/4λ) from the floating balanced point.

RF systems have practical impedance limits. The impedance limits are dependent on the operating frequency and physical size of the system. This limits our choice of choke or balun design. It also limits our target impedances.

While we can have fairly high impedances in small RF systems, melding extreme test bench impedances into larger transmission line or antenna systems is an exercise in futility. Let me do my best to give an example.

Let's consider a one foot long one half inch diameter coaxial cable suspended be vertically from a large sheet. The impedance of such conductor at 10 MHz in somewhere in the -j 5,000 ohm range. Logically, in a real world system with cables entering and leaving a choke or balun, we cannot have a useful series impedance anywhere near that value. This would be especially true if the cable were near other things, or longer. This problem also becomes worse with increasing frequency, as well as with increasing physical size.

We can specify requirements that look good in a model or on paper, but are unworkable or meaningless in real systems.

Antenna design, layout, and wiring first. Suppression last!

Some sites claim isolator or choking impedances of a few thousand ohms or more are required to isolate or eliminate common mode currents. Systems requiring thousands of ohms to mitigate common problems generally have a major design, grounding, equipment, or layout problem(s).

In general, a properly constructed layout and proper antenna with good connections and cabling will not benefit from suppression inside the building. Even a severely compromised layout, such as those with antenna's close to RF sensitive devices and/or equipment in terms of wavelength, should not be sensitive to RFI when good basic layout and wiring principles are followed. There is a side benefit to good station wiring and proper transmission line layouts. The same things that reduce RF system common mode problems reduce lighting damage susceptibility. This is because most lighting damage is s caused by common mode current, making lightning protection and RFI immunity go hand-in-hand.

Once the station or equipment is properly installed, even relatively small amounts of additional common mode impedance will offer a significant reduction in common mode. A proper system will not need more than a few dozen ohms or hundred ohms additional isolation. A poor layout might not be improved with nearly infinite isolating impedance. One thing is universally sure, if a system needs more than a few hundred ohms CM suppression the system has a major layout or wiring problem. It is best to fix that problem before adding chokes, and worrying about obtaining choke impedances impossible to achieve and maintain in a real-world system is pointless.

Place impedances in perspective. On 40 meters, 9 pF of stray capacitance is 2500 ohms. Do we really honestly think a few feet of wire would have less than 25-100 pF of stray capacitance coupling to other things? Anyone can make an isolator or choke produce a very large number in an uncluttered, controlled, test bench setup. But in the real world we have cables and wires of significant length laying in and around our desk equipment, and that changes things quite a bit. The real world is different than a zero lead length test bench setup. Choke or isolation impedances in the thousands of ohms are possible and practical in controlled layouts or environments, like at a feedpoint dangling in space. On a desk or near other large conductive objects like cables near booms or towers, more than a few hundred ohms isolation is difficult.

In most cases a combination of grounding along with very modest common mode impedance is best. In many cases when can have high isolation just with grounding alone, but grounding and cabling has to be proper!

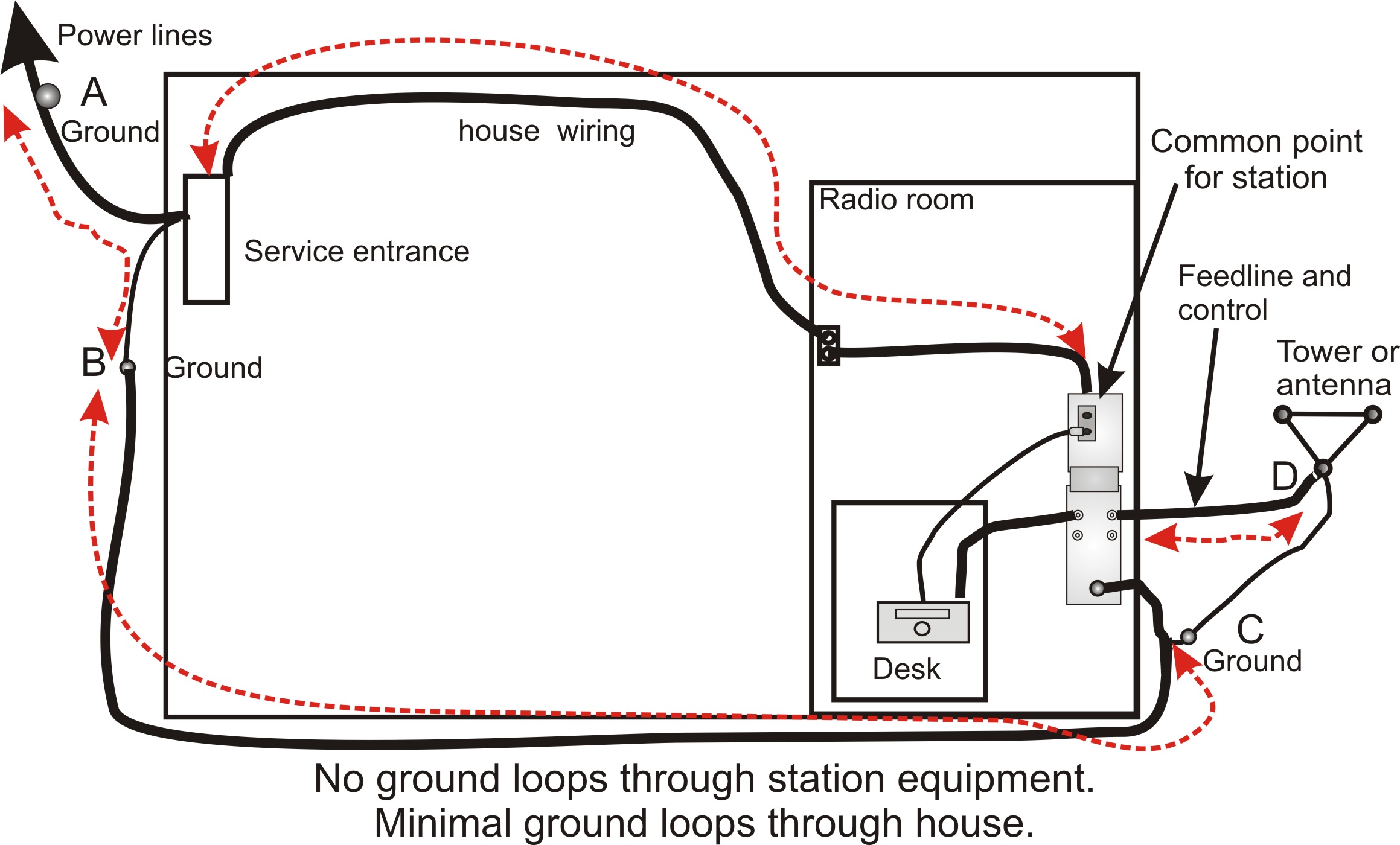

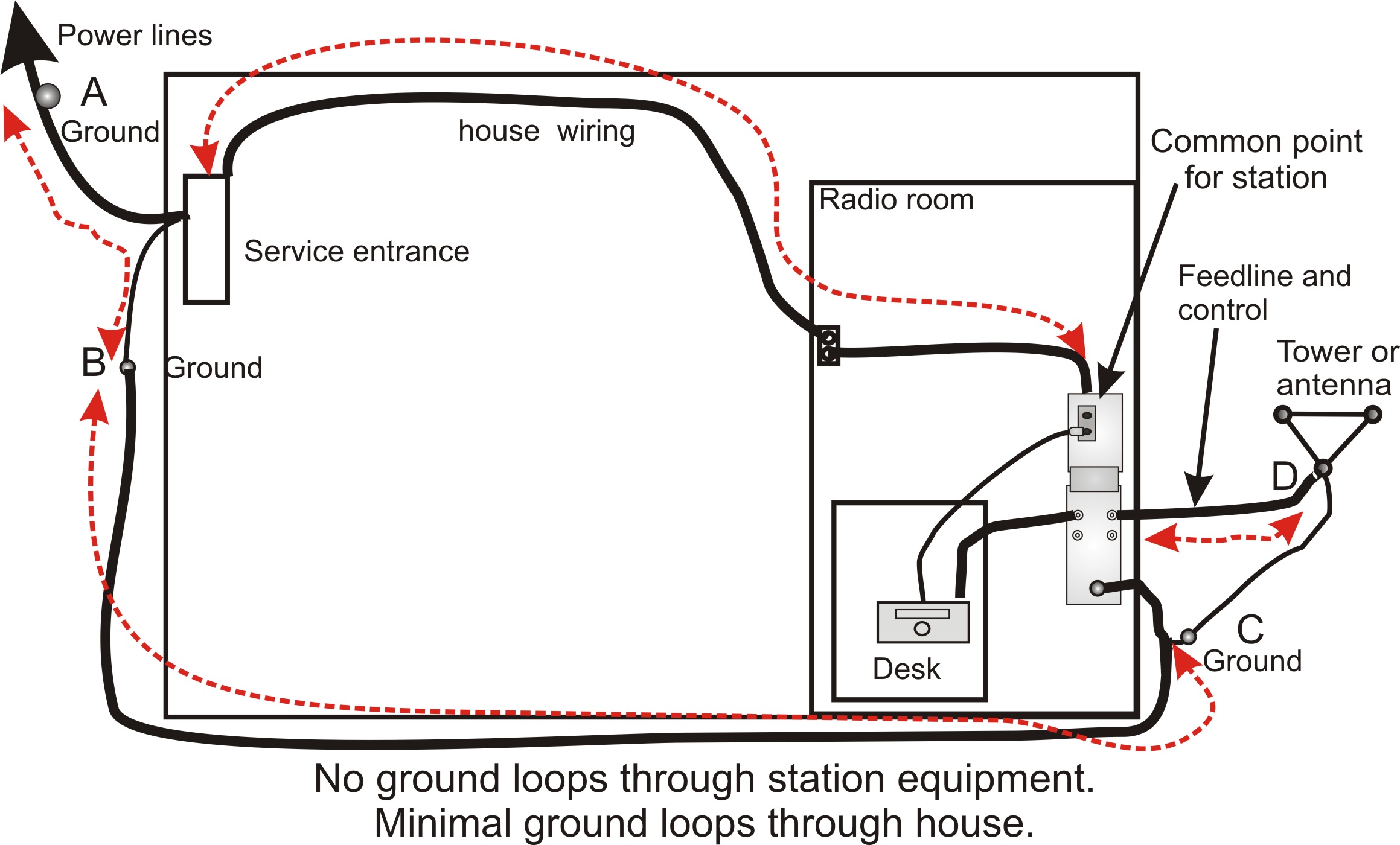

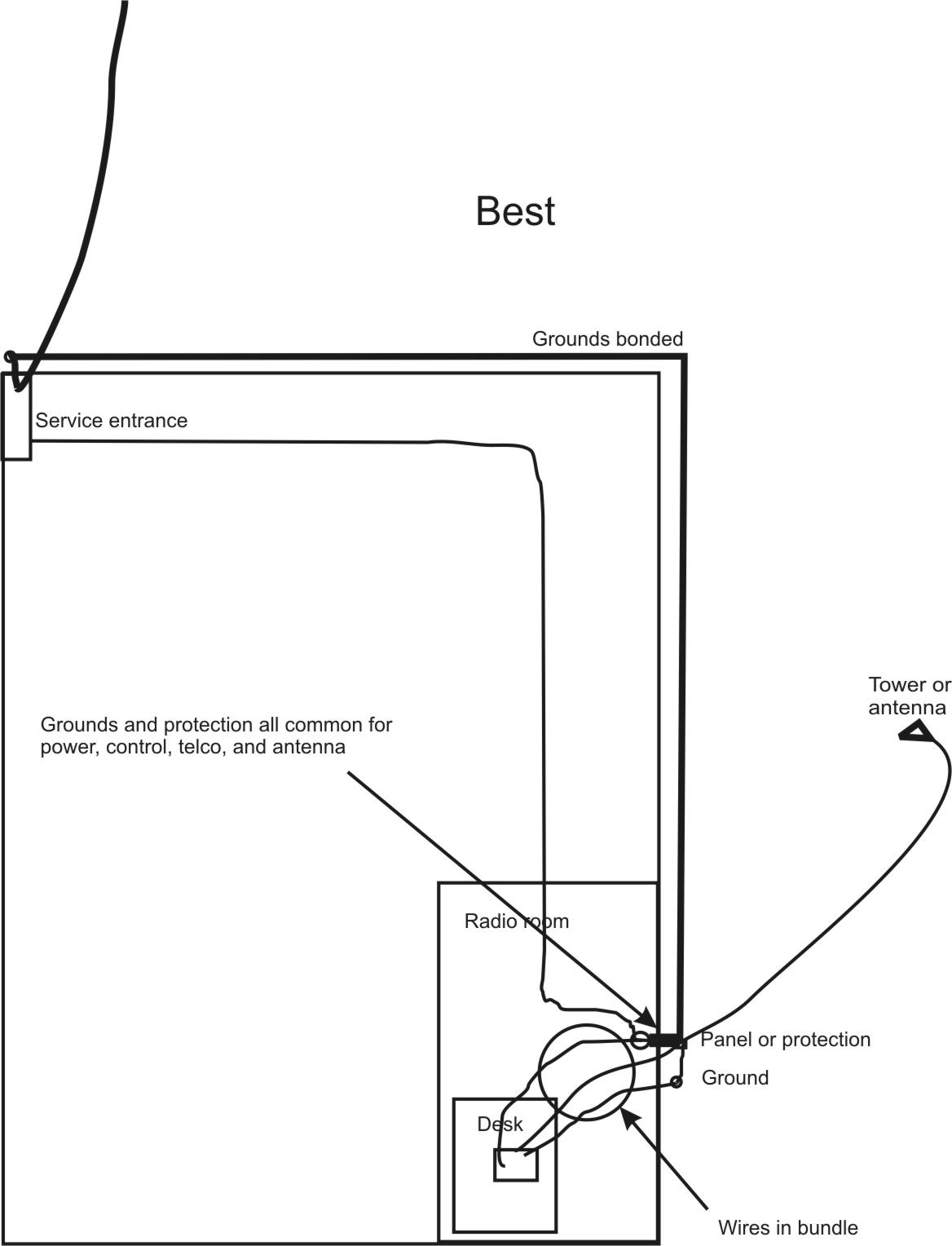

All proper installation should have a common point where cables enter for all desk functions, including power, Internet, control, and RF cables.

Shack and power mains grounds must be bonded with fairly low impedance, the

lower the bonding impedance better.

Multiple isolated grounds create

dangerous ground path loops, inviting damage or RFI problems.

Cables to the desk should be bundled and/or routed in

parallel. Bundling or close parallel routing reduces "open area" of the loop

formed by multiple conductors.

A common mode choke alters the common mode impedance of the system. The

isolation added to any system, just like the impedance required, is not predictable.

Isolation can only be measured with a great

deal of work. We can say one thing with some certainty, large values of common

mode impedance are rarely necessary.

Attenuation with the addition of a choke is a function of

the common mode source impedance, the common mode line impedance on both sides

of the choke, and the impedance of the line's ground at the equipment side. This

is not a simple system. Common mode source and termination impedances are

virtually never anywhere around

the 50-ohms a typical S21 or S12 measurements are made with. Because of this,.

measured or advertised attenuations are meaningless numbers and any blanket prediction of system

choke impedance needs are pretty much useless. All that can be said is it is

best to use a dissipative impedance (Q<1) rather than reactive (Q>>1) in RFI

suppressor systems.

In "A" below, a transmitter drives the coaxial feedline in differential (push-pull). The center conductor in this example A's 50-watt transmitter, assuming matched lines, will be at 50 volts. The shield is ideally at 0 volts to earth, being a commonly grounded point with earth. The current are equal and opposite in properly operating balanced and unbalanced lines, but in normal operation the shield being at zero volts to "ground" (or to the chassis) defines the system as being a perfectly unbalanced system.

If the system were perfectly balanced transmission line currents would still be equal and opposite. The transmitter voltages from each feeder conductor to chassis or ground, however, would be equal and opposite in a balanced line system. The line would also have two parallel conductors equally coupled to earth or ground through space.

Coaxial line behavior, from skin effect and mutual coupling from the

shield's inner wall to the center conductor, pulls all of the transmitter's

differential current to the area inside shield wall. The voltage appearing at the antenna

drives the common mode impedances of both halves of a "balanced" antenna,

pushing one side of the antenna against the other antenna half.

A

halfwave dipole, depending on construction, height, and surroundings, has

essentially equal resistances. We'll use the values shown as a discussion point.

If antenna current was one ampere and no common mode flowed on the coax, each

half of the antenna would have 25 volts to earth at the feedpoint. The

voltage developed across Rant2 causes the common mode problems, because that

voltage also excites the shield on the shield outside.

Allowing that voltage to "float", in this example to 25V, is the same as

preventing unwanted outside shield current from developing.

If Rant2 below

was near zero ohms, it would be a unbalanced antenna with a very good ground.

The better the ground, the lower "Rant2" below, the less voltage is in series with the

resistance driving the shield (B).

This system is complicated by antenna characteristics and other things. The

antenna system common mode impedance and grounding determines the source

impedance and voltage driving the shield with common mode.

The system is further complicated in that cable1's length and surge impedance

modifies the voltage and impedance at the common mode choke. In its most simplified

form, the common mode choke system looks like a pi-attenuator. The common mode

source impedance at the antenna, as modified by the cable common mode surge impedance

and

shunting leakage and ground paths modifies voltage and impedance driving the

CMC (common mode choke).

Similarly, common mode impedance into the station

equipment, likely

a pretty low impedance, determines the station side load on the pi attenuator

formed with CMC.

The attenuation and required CMC impedance quite obviously can be all over the

place. While none of us can predict the real attenuation provided by a given CMC

or predict how much CMC impedance is "enough" and how much is a waste

of effort, we can make a pretty reasonable generalization. It is very safe to

say any system requiring CMC impedances beyond low hundred's of ohms needs

layout, design, or re-wiring help more than some extraordinary impedance.

My station, where lowest possible noise floor is paramount, has never required more than a 50-100 ohms of CMC to mitigate all traces of problems. I've actually found grounding and good connections to be far more productive and reliable than dependence on a higher CMC impedances. Once I get into the dozens or hundreds of ohms without complete mitigation of noise, I know I have a major problem with shield integrity. I look for the real problem.

To understand how a balun operates and why a balun is needed, we must understand balance. We tend to think of balance only in the amount of current in each conductor of a transmission line, but that thinking can mislead or confuse us. Perfectly balanced lines and perfectly unbalanced lines alike have equal and opposite currents entering and leaving the conductors at each end!

Coaxial cables with shields more than several skin depths thick always carry equal and opposite flowing currents on the inside of their shields and their center conductors. Current direction and current ratio between the center conductor and inside of the shield in a non-radiating coaxial line is no different than currents in each conductor of a perfectly balanced ladder line. In both unbalanced coaxial lines and balanced lines, the two conductors making up the line carry equal and opposite flowing currents.

When currents flow without close-by opposing currents, we call the unopposed portion of current common mode current. Common mode currents promote or encourage external coupling and radiation. In a dipole antenna, or any antenna for that matter, common mode currents in the antenna element are responsible for radiation. In the hamshack or along a feed line, common mode current is responsible for unwanted noise ingress, RFI, RF burns, and a host of other maladies. Common mode currents, in effect, bring the radiating system into the feed line or station equipment.

Common-mode currents, or currents flowing in the same direction, cannot exist inside a coaxial cable at any frequency where the shield is several skin depths thick. Shield skin depth serves to isolate the inside of the shield from the outer wall of the shield. Common mode (same direction) currents can only flow on the outside of the coaxial cable shield. Differential mode currents, or normal transmission line currents, flow on the inner surface of the shield wall. Currents entering and leaving the shield and center conductor at each end of a coaxial line must be equal and opposite or the cable will radiate. If a coaxial line is not radiating, currents in the shield and center conductor are exactly balanced and opposite flowing. Both types of transmission lines, balanced and unbalanced, will have equal and opposite currents entering and leaving each conductor when they have minimal radiation.

What then defines an unbalanced line, source, or load? The answer lies in the voltage or electrical potential between line conductors and the environment around the line. In the ideal balanced line, the electric potential of each conductor is equal and opposite in relationship to the environment surrounding the line including the chassis or cabinets of our equipment. In the ideal coaxial line, the outside of the shield has no electrical potential difference to the environment around the line, including the chassis or cabinets of our equipment. The shield of our coaxial cables, as we commonly accept and understand, is at ground potential. We say the shield is “grounded”.

With real-world antennas, the coaxial shield connection point almost never has zero electrical potential to the environment around the shield or points further along the cable’s length. Being a less-than-ideal zero-voltage termination, shields almost always have common mode current, even if a small percentage of differential (normal transmission line mode) current. For example, the four radials of a groundplane antenna, no matter how configured or tuned, are never truly at the same electrical potential as the environment around the antenna or shield potential further down the feed line. Experimenting with a groundplane antenna, we find the feedpoint is mostly but not perfectly unbalanced. The shield is not connected to an electrically zero point. Significant current can and often does excite the outside of the shield on a groundplane antenna, with outside shield current 20% or more of antenna base current under some feed line grounding and lengths! We consider the groundplane antenna “unbalanced” and it is definitely not balanced, but it is not perfectly unbalanced.

A coax fed dipole, or a vertical with a single radial, is much worse for voltage balance. Because both antenna halves have finite and nearly equal common mode impedances, both sides of the feedpoint want to have nearly equal voltages between themselves and the environment around the feedpoint. If we could magically make a perfect single point ground appear at the feedpoint, both legs of these antennas would have very similar voltages to that reference point. Of course we can’t make that perfect reference point appear, but the feed line brings a “ground” or reference connection to the feedpoint. Third path impedance (the unwanted common mode path impedance) varies with feed line length and routing, the environment the feed line routes through, and how that feed line is grounded. While it can affect SWR and the current flowing in that path be affected by SWR, high SWR does not cause and low SWR does not prevent unwanted common mode current or RF in the shack.

Most antennas are neither perfectly balanced nor perfectly unbalanced. Most antennas are in a nether-world someplace between perfectly balanced and perfectly unbalanced. This is why a current balun, a device that floats each balanced terminal to the voltage necessary to drive balanced currents into the load, is such a desirable type of transmission line to antenna interface.

Feedlines and Balance

Traditional two-conductor feedlines or transmission lines should have very little, if any, radiation. Typical coaxial lines shouldn't have noticeable unwanted signals or noises leaking into the cable, and there shouldn't be noticeable radiation out of cables. This is true at all radio frequencies from the AM broadcast band upward through UHF, and applies to any cable with a reasonably thick single or double shield. Even cheap 80% coverage shields are adequate throughout HF in all but the most critical applications.

With unshielded

two-conductor

balanced lines,

some

small amount of

radiation from the line, or

leakage into the

line, exists. The leakage

amount should be

very low in properly installed

two-wire balanced

lines. Problems can occur with an unwanted EMI

source, or sensitive systems,

close to the

feed line. Problems with unwanted signal pickup or radiation can also occur with

very long open wire or unshielded balanced lines.

Ladder lines and

unshielded balanced RF lines should be isolated from other objects. Ideally, the

only air should be allowed within several conductor spacings of balanced

or unshielded lines. Significant levels of electric and

magnetic induction

fields surround the

line for distances of several transmission line conductor spacings. Line radiation

(electromagnetic radiation is a different mechanism) also extends out in a line

through the conductors. Unwanted radiation

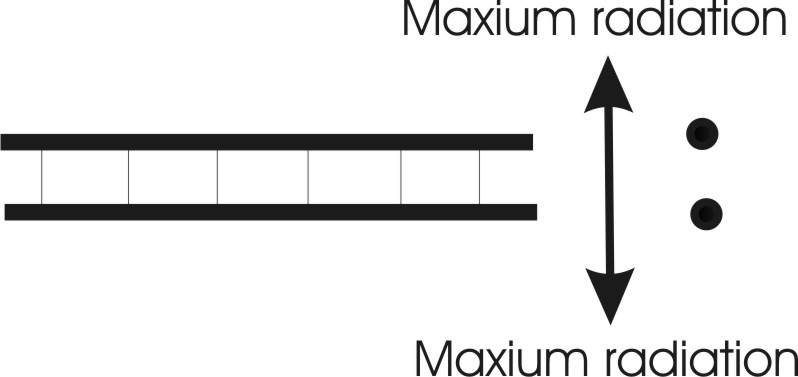

primarily occurs

in directions aligned with the plane of the line conductors, nulling at right

angles to that plane.

Even with perfect balance in a two-conductor unshielded line, some radiation occurs. The small spatial separation prevents perfect cancellation of far field radiation. The conductors carrying out-of-phase currents are not occupying the same physical space, causing a very small spatial phase delay. This means in two directions radiation fields are not precisely 180 degrees out-of-phase. The amount of phase error, and thus the level of radiation, is a function of conductor spacing in wavelengths and the direction from the line. This effect is minimized by twisting the feed line at small fractions of a wavelength.

Radiation from a perfectly terminated six-inch spaced 50-foot long two-wire transmission line on 80 meters.

Radiation of the same line at 30 MHz is 24 dB stronger. This is because the conductor spacing in wavelengths is wider.

In order to be balanced, a balanced transmission line must have both equal and opposite voltages at any particular point along the line as well as equal and exactly opposite currents at any particular point along the line. If the voltage is not equal and opposite, current cannot remain equal and opposite along the balanced transmission line. This will result in a very large increase in feed line radiation because the imperfection causes common mode currents.

In order to be unbalanced, an unbalanced transmission line must have equal and exactly opposite currents entering and leaving at every point along the line. The voltage gradient laterally along the outside of the transmission line has to be zero. If either the lateral voltage gradient is not zero, or currents entering the line are not equal and opposite on the shield and center, current will not remain zero on the outside of the shield. This will result in common-mode shield currents and feed line radiation.

To avoid feed line radiation every balanced to unbalanced transition has to be properly treated for level and phase of voltage and current.

To be properly balanced, the following must occur:

Voltages from 1 to A, and from 2 to A, must be equal and opposite

Currents into 1 and 2, at the source, must be equal and opposite

Voltages from 1 to C, and from 2 to C, at the load must be equal and opposite

Currents out of 1 and 2, at the load, must be equal and opposite

Voltages all along the line, at any point, to B must be equal and opposite

Common Mode Excitation

Common-mode current is current that is not opposed or counteracted by an equal and opposite phase current flowing at every point along the line in closely-spaced conductor or conductors, and the outside of the shield has current flowing in a coaxial line.

Any transmission line becomes at least partly, a radiating conductor if we make a poor balanced to unbalanced transition. This can be useful when we wish to use a feed line as an antenna or as a conventional conductor, but it can be detrimental to a system if we do not want radiation or reception by our feed lines. When we excite a cable as shown below, we have common mode current:

The common mode source is end-to-end on one or more conductors of twinlead

The common mode source is end-to-end on one or more conductors in a twisted pair of wires

The common mode source is end-to-end on the center, the shield, or both conductors in coaxial or shielded cables.

When we excite a transmission line as shown below we create common-mode current:

The shielded coaxial cable (top) and the parallel conductor cable (bottom) in this diagram radiates just like a single wire would do. Objects surrounding the line, like dielectrics or other conductors, couple to or interact with these lines when they are fed or excited this way. For example, adding a ferrite sleeve over the lines will add loss and/or make the lines behave differently. The impedance of the system will change, and if we are watching system SWR the SWR will change.

This is true even when currents are equal in the two conductors, and can even be true when currents are equal and opposite at one point in the system, so long as the line is excited this way.

The key to having a line behave like a transmission line is feeding it differentially (across the two conductors) at one end, having a load that maintains the differential excitation, and not applying a voltage or a potential difference across the length of one or both conductors.

This is a transmission line as we generally know it, and as dozens of reputable engineering textbooks define it:

This is differential mode, or TEM mode. This is the normally desired excitation mode when a two-wire line behaves like a normal non-radiating line that transfers energy from one point to another.

The above configuration shows a direct wire connection from source to load. It transfers voltage, current, or impedance directly along the conductors.

1/8 wave high dipole

A 1/8th wave long (35 feet in this case) coaxial feed line to the ground point on a dipole often does not need a balun! Here are feeder common mode currents for this case:

| location | amperes |

| Left leg | 0.953 |

| source | 1.000 |

| Right leg | 1.001 |

| 1 ft | 0.052 |

| 2 | 0.054 |

| 3 | 0.056 |

| 4 | 0.057 |

| 5 | 0.058 |

| 6 | 0.060 |

| 7 | 0.061 |

| 8 | 0.062 |

| 9 | 0.064 |

| 10 | 0.065 |

| 11 | 0.066 |

| 12 | 0.067 |

| 13 | 0.068 |

| 14 | 0.069 |

| 15 | 0.070 |

| 16 | 0.071 |

| 17 | 0.072 |

| 18 | 0.073 |

| 19 | 0.073 |

| 20 | 0.074 |

| 21 | 0.075 |

| 22 | 0.075 |

| 23 | 0.076 |

| 24 | 0.077 |

| 25 | 0.077 |

| 26 | 0.078 |

| 27 | 0.078 |

| 28 | 0.078 |

| 29 | 0.079 |

| 30 | 0.079 |

| 31 | 0.079 |

| 32 | 0.079 |

| 33 | 0.079 |

| 34 | 0.079 |

| 35 ft | 0.079 |

Maximum feeder common mode is only .079 amperes (out of a 1 ampere source current) with very good antenna current balance. This is without any balun!

The same dipole 1/4 wave high:

| location | amperes |

| left side |